"AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN"

☻

"AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN" ☻

Writing from Columbus, Ohio

I'm autistic and I’m reclaiming my time.

Photo Credit: Nick Fancher

Aggressive. Condescending. Egotistical.

For years, these words stuck with me, thrown by managers – not leaders – who didn't know me.

I’m #ActuallyAutistic.

Before my diagnosis last year, after a lifetime of struggles, challenges I couldn’t name, and endless attempts to do the things I saw those around me doing – I felt like a complete failure.

When I was writing documentation, I wasn't trying to be pedantic; I was helping teammates who’d said they found the lack of clear processes confusing. When I shared about a new investment, I was trying to show my buy-in, not saying, "Look at me."

But when it came from me, it was received differently – often leading to criticism or even punishment – and I could never figure out why.

Once, I went into what I expected to be an interview, and instead it turned into a dressing down for “three red flags” of my personality and why the job description was changing.

Before my autism diagnosis, dear reader, I thought that was ALL me.

Empathetic. Creative powerhouse. Leader. Those are the words I’m carrying forward. And autistic.

This isn’t exactly how I planned to share this with each of you, but given recent events, now's the time to use my voice. I was diagnosed last year after a lifetime of pushing against the current and not knowing why. Communication challenges, sensory overwhelm, anxiety – it was all there, but I never saw it in a way that made sense to me until I started researching autism.

Once I began learning about autism, leading to an assessment and diagnosis (& ADHD – once a high achiever, always a high achiever, I guess!), I haven’t felt this light – ever. Everything makes sense.

I am different, but OK.

"This explains so much!" If that was your thought, it was mine too. But it doesn’t mean the process of self-discovery and acceptance was easy, fast, affordable, or accessible, especially in a world that so clearly does not want a person like me to exist.

"Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light." – Brené Brown

I’ve always been autistic. It wasn’t in water or vaccines; it’s in my genes. And I do take Robert F. Kennedy's words seriously because I know someone out in the world does. You don’t get to claim you were misquoted when you were dehumanizing people, and then turn right around and continue to dehumanize them. Putting people like me on a list? Does that solve anything, or is it supposed to intimidate me? Because in my view, it does neither. I’ve always been right here, and these same folks who claim to know people like me rarely bother to speak to me, if at all. I did live in Appalachian Ohio, and I certainly never saw JD Vance.

Being autistic, in my world, feels like being water. It means constantly shapeshifting to the form of whatever vessel I find myself in, and still never quite fitting – making a mess, spilling, being messy and imperfect in the pitcher or cup or whatever other container is "the norm." It’s the feeling of a million little interactions, moments, stimuli that pull our attention in different directions, pull out our individual molecules, the hydrogen from the oxygen, and we still have to have that to the boss by EOD. It’s having all of these words and never being able to put them in the right order when it feels like I most need to say something plainly. It feels like saying something plainly and being told it was too blunt.

Masking is how many cope. Like changing your flavor to additives of others – you'll find many who still don’t quite like your taste because it’s not your authentic self, and you always feel at odds. For me, being autistic feels like fitting everywhere and nowhere, being wise and old and young and inexperienced. It feels like the ultimate contradiction.

Autism is loving yourself and being told it’s too much.

Like water, different neurotypes add so much nourishment to our communities, teams, and friend groups, yet too often the effort goes overlooked. Like water, we try to go with the flow, but when too much pressure builds, it leads to a meltdown – something I’ve even been shamed for at work when put under months of extended stress. That doesn't undo the garden of seeds I've cultivated anymore than anyone else's moments of extreme stress.

Unexpected tears in front of bosses, panic attacks every Sunday night, and trying to heal from obvious PTSD at the same time doesn’t really work. You can talk about productivity, but that doesn’t matter when a person’s brain is overloaded and can’t process additional information at that point. These are the things that stick with the humans on your teams – much more than swag.

That’s all part of me, not a choice. It’s how my brain functions, how my nervous system functions. To push against that day after day, to delight other people – whether small interactions at a counter in a store, a meeting, a Google Doc, or on social media – can be draining when I'm not properly supported in return.

Like water, my energy and ideas all pour from the same container. As an autistic person, I have to protect my water. I have to protect my energy, my resources, otherwise that mental capacity is drained by masking. That water can only be refilled with rest, regulation, and proper support.

2025 has been been an illuminating, sad, confusing, and hopeful time. For me, so many past experiences make sense in a new light – lessons, mistakes, all of it. There are times when I clearly misread a situation, others where I clearly lacked the support I needed. I'm sorry for both.

Yet the more I know about myself, the more I love myself. All I can do is commit to being even better going forward. In one workout, an instructor said something to the effect of: "You broke my heart… thank you… look at me now." I like that thought. 💖

Photo Credit: Nick Fancher

I know the courage I gain when others speak vulnerably. If my story lends a bit of courage to someone else right now, it’s not even a choice. For the folks who wish I would talk more but don’t want to hear what I have to say, I’m reclaiming my time. With the gifts I’ve been given, I can only hope to pay my blessings forward.

My mental health and well-being are mine. I turned down a $200k salary to prioritize myself, and my mission in life is to help everyone embrace their creativity, so we all can love and learn and grow and process grief through creativity in all its forms. Art therapy exists for a reason.

If you want to be sure your autistic and allistic creative teammates have the best support for their brains to generate actual innovative ideas, to ensure they aren't crying in between meetings, having panic attacks every Sunday night, and healing from years of PTSD – send me a message. We rise by lifting others up.

"May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears." – Nelson Mandela

Are You Composting?

In an encouraging bit of news, I recently read that solar panels are being built on more landfills in U.S. cities.

From Good Good Good:

Such projects not only help cities meet ambitious renewable energy targets, but they can also reduce local power bills and generate revenue for city coffers by leasing out idle land.

"It makes (the production of clean energy) tangible for residents, maybe makes it cheaper... and shows that they're trying to actively reduce their local emissions," said Matthew Popkin, a manager with think-tank RMI's U.S. program who leads its Brightfields Accelerator partnership, which helps local governments convert brownfield sites for clean energy use.

While the number of solar parks being built on landfills has increased in recent years, there is still huge untapped potential, industry specialists say.

There are at least 10,000 disused or closed landfills across the United States — and most are publicly owned, Popkin said.

He and his team were able to analyze about 4,300 of those sites and estimated that those alone could produce 63 gigawatts (GW) of electricity — enough to power 7.8 million U.S. homes.

I haven’t heard anything about this in my community, and given there are 10,000 landfills, this seems like a potential energy solution with significant upside.

But in this good news, there is a darker story. The reason why they’re resorting to building solar panels on landfills is because landfills are awful and can’t be used for anything else.

And that’s for landfills that are out of commission.

Landfills in use are risky and dangerous and pose potential health issues to workers.

It gets worse.

Later in the story:

Such projects could also help address long-standing grievances over the location of landfill sites, which historically have tended to be built close to Black and other marginalized communities.

One study found that "race was the most significant factor in siting hazardous waste facilities, and that three out of every five African Americans and Hispanics live in a community housing toxic waste sites," according to a U.S. Department of Energy primer on environmental justice.

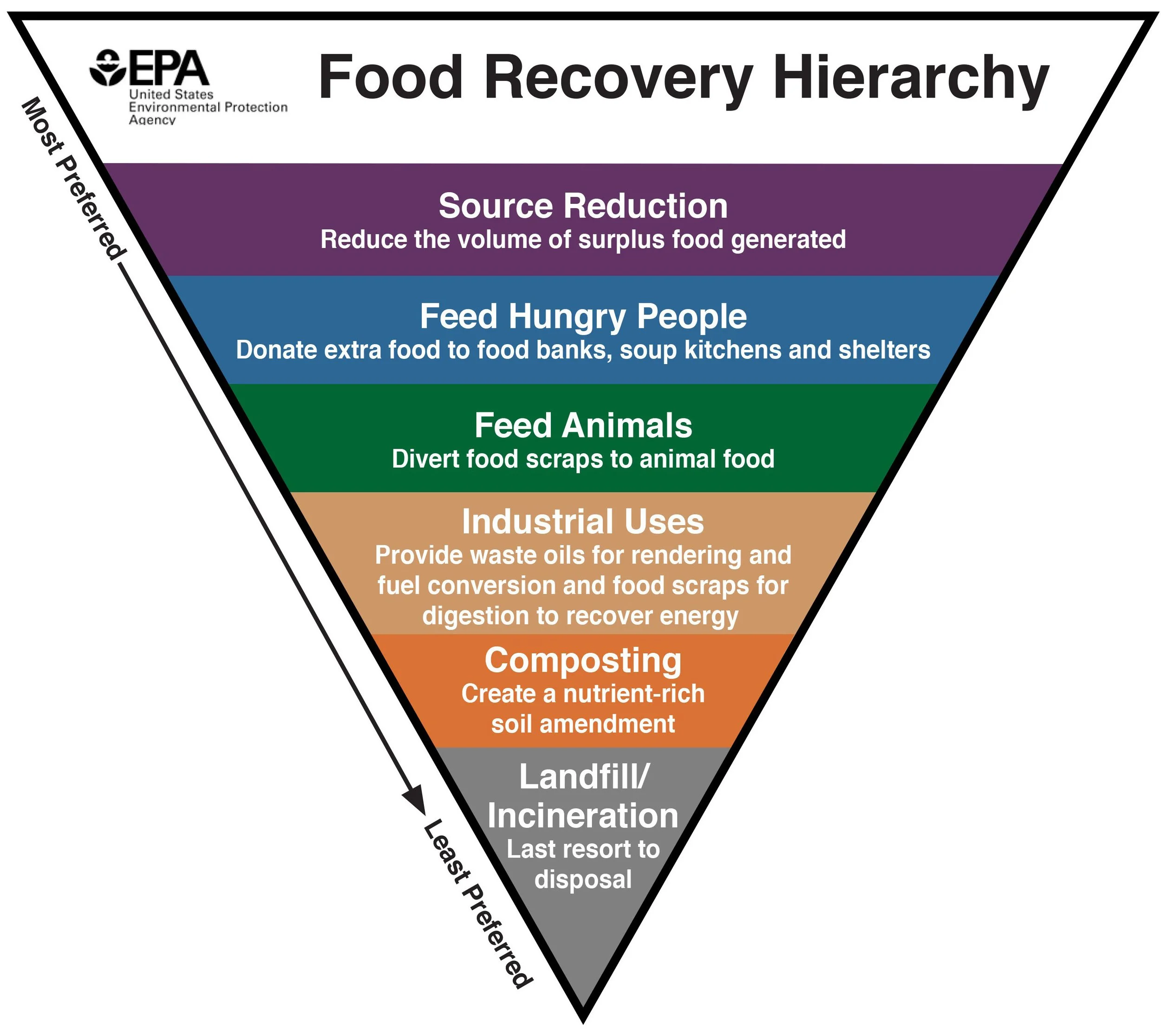

Looking for ways to redirect waste from landfills, even a little bit, so as not to feel helpless, I turned to composting.

Composting is the process of turning organic waste into a nutrient-rich soil amendment and fertilizer.

And it’s lingered in the back of my mind for far too long.

As our family has grown, so has our awareness of the waste we generate – it’s impossible to avoid as a family of five. As I’ve taken more time to learn how composting works and how it could fit into our lives, I’ve found myself eager to spread the power of this practice with others who may be curious.

If you’re not currently composting, some quick benefits:

Reduce Waste: Composting diverts kitchen and yard waste from landfills and turns it into something you can use.

Get Free Nutrient-Rich Soil, Save Money: Compost creates a nutrient-rich soil amendment that enhances plant growth and reduces the need for expensive fertilizers filled with harmful chemicals.

Reduce Your Carbon Footprint: Composting reduces the waste we send to landfills, where overflowing dumps contribute harmful methane emissions to the environment.

Boost Biodiversity, Save Water: Healthy soil supports a diverse range of insects that aid in plant growth, and your compost-enriched soil retains moisture more effectively, so you can water less.

Community Building: Composting creates community through shared composting initiatives, knowledge sharing, and time to connect.

In short: Composting enriches the soil and reconnects us with everything around us.

Taking small steps toward a more sustainable and mindful way of life is a gradual but active process – living a little more mindfully each day is the goal.

And thankfully, for us beginners, there are a lot of experts along the way more than willing to help.

Cassandra Marketos, writer of a fascinating newsletter on everything compost called The Rot and author of the forthcoming Compost This Book, is one of those experts, and she joins us today to answer some burning questions when it comes to composting.

Cass and I have known each other for years – when I was leading content at Big Cartel, I hired her to write for us, and she always produced great work, including this incredibly insightful essay on what makes work meaningful that we published online and later in a zine. I’ve been following her newsletter and learning in attempt to get over the hump and start composting myself, and when she announced her book, I thought it was the perfect time to share with you.

Ultimately, I made this book for all the people out there like me, who don’t do well with spreadsheets or on tests, and who have been typically alienated from things like “science” and “chemistry” in traditional school settings. “Compost This Book” focuses on learning through action, practice, observation, and—most importantly—making huge mistakes. Lots and lots of huge mistakes. I want people who read it to feel empowered to mess up, and I also want them to feel invited into deeper learning on their own terms. – Cass Marketos

Based on Los Angeles, Cass has a passion for rotting as she works tirelessly in her community to help others learn about composting and the power of diverting waste from landfills.

She chatted with me in anticipation of her book and provided great insights to make composting less intimidating and more fun – I don’t know about you, but crushing eggshells sounds like some great stress relief!

What are the biggest benefits of composting?

I think a lot of the environmental benefits of composting are broadly known. Composting your food waste reduces methane emissions from landfills. It takes "garbage" and turns it into a meaningful soil amendment and fertilizer. However, the biggest benefit that I see from composting is the mindset shift in people who take up the practice. It changes how folks act as consumers. Once I get somebody hooked on composting, how they buy stuff changes completely—they are more aware of how things are made and less interested in buying things that won't biodegrade. In general, they become more invested in buying less. It's really amazing to witness (and I've definitely experienced this shift in myself, as well). Having a more fundamental and tactile understanding of ecological processes—and more awe and delight in nature—really tend to make you more aware of the connection between "buying tons of stuff" and ecological destruction, and you naturally become more thoughtful about your purchasing choices. It's a beautiful and, I think, often underexplored benefit of composting. :)

What are some common challenges beginners face when composting? What tips do you have to avoid those issues?

The "ick" factor. Far and away, that is the most common challenge I help beginners overcome. They think of compost as a pile of rotting food and a bunch of bugs, which - hey - they're not totally wrong. The best way to overcome this challenge, though, is just to help people shift the frame of their thinking. It's not rotting food, it's "becoming soil." And that soil has value that you can then witness in practice and be part of creating. Bugs are also often a sign of a super healthy pile—one that is full of active microbes that are building nutrition and turning all of your food scraps into vital, living soil. I know you might be reading this and thinking "No way, not me - bugs are gross!", but I promise you that everybody starts out that way, and once you get a feel for your pile, you simply cannot think of bugs and food scraps in the same way again.

What can you do to avoid attracting unwanted critters while composting?

Your pile will *always* attract certain critters, like soldier flies and beetles and worms and etc. These are signs of a healthy compost pile and if you *aren't* seeing these types of critters—I'd be concerned. When it comes to the bigger guys like rats and raccoons, though, a well-managed pile is your best defense. Chop food scraps up thoroughly and bury them in the pile versus just throwing them on top. Make sure you're using the correct ratio of carbon (twigs, shredded leaves, wood chips, shredded cardboard) per addition of any food scraps. You can also pee on your pile and/or leave around bits of your hair or pet's fur. These odors can deflect unwanted advances from curious animals.

Any tips for working composting into a busy family or work schedule? Suggestions on what's most important to focus on vs. what's not?

My first tip, the one that I think is the most important, and the biggest one, is also categorically the hardest for people to follow, which is this: let it go. Ha. Let the idea of perfection and "doing it right" go and let it go completely. Be open to messing up and doing things wrong and learning. Accept that sometimes you will have lots of time to work on your compost and sometimes, even for months!, you won't have any time at all—and that's fine. You may end up with a few critters or a bit of an odor, but if those things happen, you'll be able to address them, and it's okay.

Okay, phew.

Now that that part is out of the way, the best thing you can probably do to keep your compost manageable and productive is prep your materials. I cannot undersell the value of well-shredded materials being added to a compost pile, it just makes everything decompose so much faster, which really helps mitigate issues like odors and unwanted animals. I would prioritize shredding materials even over stuff like turning the heap. Pre-shred anything you add to the compost pile & always cover with some layer of carbon, whether it's a bunch of wood shavings (this is my preference) or cardboard or whatever else. :)

What tips do you have for composting with a large family?

When you are dealing with a lot of food waste, taking the extra time to prep your food scraps for the pile can make a huge, huge difference. Chop everything up into teeny, even tinier pieces. Crush your egg shells. Break the stems from that flower bouquet into smaller pieces. The more you chop and shred stuff before it goes into the pile, the easier you are making things for the microbes in your compost pile. They have more surface area to go to work on and will be able to break things down much more quickly. That means your pile will be very efficient and can accept a lot of food scraps without getting too big or too overwhelming. (A compost pile that is really cookin' will reduce in size by about half over the course of a week.) It does take a little extra work on the front end, but it's totally worth it.

Are there any exciting advancements on the horizon that could change the composting process for individuals and communities? Tech, legislation, or anything else to watch?

There has been a lot of recent legislation around composting, with tons of mandates being passed down in various cities around composting food scraps versus sending them to the landfill. All of this is great. Legislation unlocks funding, which helps create infrastructure, which helps support people in changing their habits, which builds public awareness around waste management, which then can, ya know, probably change the world.

I am generally less excited about "compost tech." For the most part, compost devices are expensive scams and totally unnecessary, built to serve our pre-existing (and harmful) assumptions about waste and waste management (the same assumptions that have directly lead to so much of the pollution and environmental abuse that has now put our planet at such a precarious tipping point). When products are built to serve our presumption that we shouldn't have to deal with our own waste, and that our waste is "icky," we are continuing to alienate ourselves from our responsibility to our environment. We *should* be accountable to our waste streams. We should understand and have to experience the consequences related to what we buy and how we shop. I don't think so many people would be so cavalier about fast fashion ("it's no big deal!") if we had to deal with landfills and textile dumps in our backyards, for example. (And to be clear, a lot of people do not have the luxury of NOT having to deal with those things.)

In what ways could community-based composting initiatives play a key role in shaping a more sustainable future?

Education, awareness, and accountability. Accountability being the big one. (See my above rants.)

Understanding how much waste comes from your community and having a hand in directly dealing with it is incredibly empowering, particularly if you're turning that waste back into something that has value and beauty for your neighbors. I work at a few community compost hubs across Los Angeles where we accept food scraps from local businesses and then give back the finished product to the community for free. The amount of joy it generates is addictive. When we can do things that create joy around sustainability for people, that require them to work together and make something together, then I think we are really creating the building blocks for something that looks like "a future." :)

Thanks to Cass for sharing her time with us! Pre-order Compost This Book and when you’re finished reading, you can use the book itself to start your very own compost pile!

2-Minute Warning: Your Brain Needs This

Meditate to live a healthier life, focus better, and have better ideas.

2 minutes of calm can lead to profound effects: reduced stress, boosted focus, ignited creativity – all leading to an improvement in your overall wellbeing.

It's like weightlifting for your attention span. And the trick is that once you do 2 minutes regularly, you’re going to want to do more.

You only need yourself, your breath, and a phrase or mantra if you’d like.

For me, peace through practice has become a favorite, reminding me that the journey itself determines the destination. Fittingly, for someone with a background in brand strategy, peace through practice comes from a Nike tagline – an important reminder that inspiration is everywhere.

And I love that it’s a reminder you can’t busywork your way toward peace, happiness, and health.

To meditate:

Close your eyes

As Peloton instructor Camila Ramón likes to say, “Inhale everything that you are, and exhale everything that you feel you need to be.”

Take a deep breath

Let your thoughts flow without judgment – like clouds passing by in the sky

Exhale

This simple practice can lead to significant changes over time.

Meditation isn’t only about relaxation – it trains the mind. By training the mind to focus and redirect thoughts, we develop a positive habit of mindfulness that leads to better, healthier choices throughout the day.

Looking to boost creativity? It’s the same idea.

Capture daily life through writing, photography, painting, or any other interest that sparks your curiosity. Write for a few minutes a day without judgment or expectation, and then review your writing to discover patterns and ideas worth further exploration after a few weeks.

Creativity, like peace, is a muscle grown through practice.

This month, I invite you to think about nothing and embrace the practice of meditation.

It's ok to let your mind wander – that's all part of the journey towards peace.

Incorporate meditation into your life, even if it's just 2 minutes a day, and watch how it enhances your creativity, focus, and overall wellbeing. There’s even a website that makes it easy to track your time and remember all you need for this simple but powerful practice: 2 minutes.

Try it. You deserve peace. ☻

How I Lost 100 Pounds in 18 Months: Good Decisions Compound

People pleasing almost killed me. The journey of loving myself first has been a revelation.

At the start of the pandemic, I weighed over 300 pounds.

Like I imagine many others do at that size, I stopped checking the scale as often, but the highest number I ever saw was 311.

My unhealthy lifestyle was exacerbated by my tendency to be a people-pleaser, often putting my own needs and mental health last.

This attitude was, in part, the result of growing up as the black sheep in a challenging environment.

I’m the product of an unwanted pregnancy. My father split before I can remember. At many key moments, I was left to raise myself – often with a heavy dose of Mr. Rogers on TV, reading any book I could get my hands on, and later spending hours on the internet.

My childhood had plenty of adversity, abuse, and isolation, but among my loneliest moments was during my sixth grade year, when my mother sent me to couch surf with a friend for the school year.

From that day forward, what little time I was around family, I was expected to act a certain way for acceptance and love. Growing up in small town Ohio where the KKK once literally marched the streets in my lifetime, it simply wasn’t safe for a queer Black kid like me to exist.

I fit no one’s definition of normal; my mere existence is a political statement to some.

To say I grew up in survival mode would be an understatement.

The child in me tried to manage the world through impossible feats of perfectionism, as many do, thinking if I performed a little bit better (but always to someone else’s volatile, unwritten standard), I’d find acceptance and love.

But it never came. At least, not from there.

It took me 33 years to realize it was an impossible game to win. And those tendencies – caring what everyone else thought first – were driving me off a cliff and into an early grave.

Two years later, at 35, I now realize I am worthy of love just because. And loving myself first opened the path to a happier, healthier lifestyle.

I’ve seen the effects of not taking care of your physical and mental health through my own eyes.

Yet it was the shock of the pandemic that pushed my wife Ali and me towards the realization that only we have ownership over our health and wellness.

What I’ve since learned, as Dr. Julie Gurner of Ultra Successful says, is that “Accountability is a form of self-respect.” Starting in lockdowns, we focused on our health obsessively, taking our accountability into our own hands and achieving a new level of intensity.

I set an ambitious goal to lose at least 90 pounds, with a stretch goal of losing 100+ pounds, and I was committed to seeing it through.

But I’d never done this before. I had to learn as an adult how to care for myself. Through this, I also learned how to avoid being defined by the self-limiting beliefs of others.

“Anything is possible” is more than a slogan.

Over time, my health and fitness journey taught me the power of consistency, the necessity of boundaries, and the importance of self-care.

Intermittent fasting changed my life

The decision to go all-in with intermittent fasting in the summer of 2021 triggered a major shift in my perspective.

The physical challenge was undeniably tough, but through the process of not eating three overstuffed meals a day plus snacks, I learned that I am not a prisoner to my thoughts or desires. I am in control of them.

Or think of it like this, as Peloton instructor Kirra Michel beautifully illustrated in a recent meditation:

You are the blue sky.

Emotions are the weather.

Over time, I reduced my food intake to one meal a day and focused on clean eating with simple ingredients. That meant I would generally fast 20+ hours a day, often 23 hours a day. Drinking a lot of water – around 100 oz. on an average day – was it.

In the earliest days of my weight loss journey, I would ask myself, “Is it the body or the mind?” when I was trying to determine what I might need – whether I felt a hunger pang, a pain in my body, or a feeling rising that I needed to deal with.

Sometimes the mind tells you you’re hungry, sometimes it’s your body.

You should generally listen when it’s your body.

Your mind? More often than you might think, it’s safe to ignore.

Intermittent fasting gave me what felt like a superpower to almost instantly distinguish between the two.

My longest fast was 43 hours, an experience that I didn’t know I had in me – that again widened my view of what was possible. The clarity that comes with such a long fast is refreshing. You feel how your body is supposed to operate, and you become more in tune with your needs.

During those two days, I lost 7 pounds. While some of that was water weight, it’s still shocking to see what you can accomplish by setting clear goals and working towards them with perseverance.

I used the Zero app to track my fasts for well over a year until it became a natural part of how I operate.

By learning that it's not only the body, but the mind as well, I turned what was inside me into fuel, propelling myself to better health – literally. From my non-medical understanding and in simple terms, fasting helps your body burn fat for energy instead of storing it for later. And it works when you follow a plan that is safe for you.

You must always work

Jonah Hill’s 2022 documentary Stutz played a pivotal role in reshaping my outlook on the intersection of work and wellness. The film dives into the life and philosophy of psychiatrist Dr. Phil Stutz, Hill's own therapist, through a series of deeply personal conversations; how the film explored vulnerability and mental health resonated in a way that few do.

“You can’t move forward without being vulnerable,” Dr. Stutz tells Jonah in the film. So that’s what I’m doing here.

But in addition to that wisdom, there’s one thing I think about every day from this film:

Work is constant.

And we choose what hard work we do.

Stutz made me realize that I want my energy to be directed towards the things that fulfill me – hard work, exercise, meditation, and healthy relationships with my wife and children. The film's candid look at personal wellness, self-doubt, and therapy underscored the power of personal choice in our journey and how it impacts our health – which impacts everything else.

And while each person’s journey and medical needs will vary, the film is a powerful story of what it means to prioritize wellness through your choices and commitments.

“Take action, no matter how frightened you are,” Dr. Stutz shares in the film, “If you can teach somebody that, they can change their whole life.”

But you should know the work never gets easier, as Duke Women’s Basketball Coach Kara Lawson told her team.

To succeed, you must get better at handling hard.

Each pound is harder to lose than the last, but I’ve learned to love the hard work, discipline, and dedication to seeing my goals through.

By making small but meaningful adjustments to my diet and persistently sticking to a realistic exercise regimen, I experienced noticeable changes quickly – I lost 40 pounds in less than three months.

For diet, in addition to intermittent fasting:

I cut out red meat

I eliminated nearly all sugar

I stopped eating fast food

But that was pretty much all I changed about my diet. I kept a lot of my favorites, and didn’t punish myself through lack of food or unrealistic meal plans.

Instead, I restricted my eating window with intermittent fasting, and tried to make my diet a bit cleaner each week.

As I felt better, I could move more. Once I felt this good feeling, I started chasing it daily with walking and stretching. Then I added yoga and cycling (even on bad weather days thanks to Peloton, removing another potential excuse), and I started meditating daily.

To make this habit a routine, I scheduled time in my calendar – even as little as five minutes to meditate before a work meeting. Working in the fast-paced world of tech startups, taking five to meditate is a powerful way to manage stress, and once you do it I’m convinced you’ll feel the same.

Stretching daily gave me a newfound appreciation for life and freedom. It eased my aches, prevented new pains, and improved my flexibility and strength.

Moving your body for even 20 minutes each day is better than not moving. Even when you’re tired, a little extra effort goes a long way.

Although each pound gets harder to lose, the added movement and motivation in every other area in my life pulls me forward through each hard moment.

Over time, these small changes compounded and resulted in a significant weight loss – I lost 100 pounds in just 18 months.

To this day, now two years into my journey, I’ve continued to lose weight, build muscle, and maintain a healthy lifestyle while working off the remaining weight I’d like to lose.

But the journey wasn't only about a number. It was about reclaiming my life, setting boundaries, and prioritizing my health.

For the longest time, I felt like I had to work hard to prove others wrong.

Now I work hard to prove myself right.

Good decisions compound (so do bad ones)

When my weight loss really kicked in overdrive, it was for a simple reason: I set a clear intention to begin treating myself like an athlete.

I’ve always wanted to be deeply involved in athletics. I was the kid drawing up plays in the dirt on the playground and in my notebook everywhere else.

Despite being an athlete at heart, certain circumstances prevented me from being active for years. I missed out on organized sports due to a number of reasons from financial constraints to not having an adult willing to sign the permission slip to participate.

It was a lonely time as I became even more disconnected from sports – one of the few things that brought me health and joy. I never got to participate in high school or college sports, and my situation further emphasized the lack of good food role models in my life.

Before I knew what was happening, I was in a downward spiral.

Fast forward to the end of 2022 – while attending a Small Giants session, the speaker emphasized the positive impact setting an intention to start the year can have.

I decided to give it a shot, and set myself up with a refreshed commitment going into 2023: to train like an athlete for the first time in my life.

I use Peloton and Apple Fitness+ daily so I can try a variety of workouts – such as shadowboxing and strength training in addition to yoga and cycling – and I make sure to move 20-60 minutes every day.

Yes, even when I’m sick, because movement brings me back to health. The days you don’t feel like working out but still do can make the biggest difference. You don’t hear about great athletes taking days off, you hear about them finishing their workout before the rest of the team shows up. That persistence pays off.

And once I heard Dr. Wendy Suzuki describe 20 minutes of daily exercise as a “bubble bath for the brain,” I was hooked.

Following positive voices while removing negative ones from my life and social media feeds, I slowly broke free from the chains of my past. I learned to love the hard work, because that's what led to good results. I embraced growth and pushed further outside of my comfort zone, because that’s where true growth exists.

And I learned that I could say what was on my mind, because the people who support me want to hear what I have to say.

With the support of my mentors, I drew strong boundaries, and I decided to love myself first.

To overcome my people-pleasing tendencies and take back control of my own life, I had to take a full account of what drained my energy and what restored me. That even meant ending relationships with people from my childhood. This was challenging and among the hardest things I’ve ever done – but as I focused intensely on the things that made me healthy, I found myself not only digging out of the hole but smiling in the sunshine again.

For the first time in my life, I was fully committed to myself.

I put more focus than ever on how I felt, and how my needs were being met (or more importantly, in many cases, weren’t being met).

This decision was pivotal and it still pays dividends. Each day I get even healthier is further proof to me: Good decisions compound.

Being in a healthier place now, I can use what I’ve learned to spread awareness and help others gain a better understanding of how to care for their physical and mental health, too. I’ve seen friends get inspired to move along this journey, and that keeps me moving on my hard days. Yes, there are a lot of tears on this journey – more than I think most of us would admit.

Throughout this journey, I’ve drawn inspiration, strength, and guidance from mentors, coaches, and leadership development programs like Small Giants. It’s important to maintain a strong network of positive influences. Surrounding yourself with successful people who’ve often been through many of the same situations can help each part of the process seem a lot less scary.

We all only have so much to give, but we can give more when we are well, and even more when we are well supported.

Through this, my mentors have helped me develop a resilience I didn't know I could posses. But as Ali, my partner who has supported me through thick and thin always reminds me, “When you focus on the good, the good gets better.”

And now I want to help others focus on what they are capable of when they are fully seen.

For me personally, taking care of myself improved my relationship with my kids immensely. I can confidently say that I set a better example each day, because as I’ve become more active, so have they. (They can’t keep up with me on a bike now!)

They’re in hockey and soccer and gymnastics and all kinds of activities that I can experience for the first time as family. This is what it’s all about.

But growth is a process, and certainly not a straight line. So it’s important to step back and reflect. On hard days, what has changed?

In 2023, we have more fun and go more places because I’m in less physical and emotional pain. I’m more available for their needs because there’s less anxiety. I’m more confident because I finally recognize my smile in the mirror.

We’re building a home that is calm and supportive, where each person is loved for who they are inside and out. That includes me.

And now I can say without a shadow of a doubt, taking care of those around you begins with taking care of yourself.

Takeaways from my journey that may help on yours.

Establish a routine: I made it a point to include physical activities like stretching, yoga, meditation, and cycling into my calendar. For 87 straight weeks, I've exercised with increasing frequency, building my fitness levels steadily. “Repetition creates growth,” as Peloton instructor Emma Lovewell wisely put it.

Prioritize your health: Make time for exercise in your schedule. It is as important as your work and family because your fitness and health allow you to be there for both effectively. Make it easy – remove the opportunities for excuses to creep in.

Remove negativity: Removing negative influences is crucial. Meditation and mindfulness practices can help you manage and process your specific challenges.

Seek support and accountability: Having an accountability buddy makes a world of difference. In my case, my wife Ali played this role perfectly, and I will endlessly be grateful for her support. Together, we lost over 150 lbs. and motivated each other throughout this journey, especially on our hardest days.

Develop personal mantras: Create motivating phrases for those hard days. One that worked wonders for me was: "Make the next right choice today."

Focus on how you feel: If the scale isn't moving, it doesn't mean you should stop working hard. Shift your focus to how your clothes fit, how you feel, and your energy levels. I’ve ignored the scale for long stretches because I’m confident I’m still making the right choices each day.

Adopt a balanced lifestyle: As one of my coaches advised, "Don't be about one thing, be about everything." Balance in all aspects of life is essential for a healthy lifestyle.

Embrace small, repeatable changes: Try cutting out unnecessary sugar and drop the fast food. I’ve focused on small, repeatable changes that I can make day after day, stacking the progress on top of each other.

Seek the right medical advice: Continually seek the right doctors and medicine. If the first isn't right, don't give up – your health is worth the search.

Remember, it's your life and your body.

Take ownership and love yourself like you'd love your best friend. This journey towards better health and fitness is as much a mental challenge as it is a physical one. Believe me when I say – every step is worth it.

The Act of Creation in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

The act of creation is both constructive and destructive. It requires taking old ideas and combining and distorting them into the new. It is not merely enough to replicate what has come before – in fact, that’s so bad we have all kinds of copyright laws and plagiarism rules to prevent it.

Artificial intelligence makes that point almost moot now. With enough time a computer can create every variation of every sentence ever possible.

What is an original idea then? The creation of something more, a whole with a sum greater than its parts.

Everyone is creative. The urge to create is inside of us, whether it’s an art project or the meaning of a life event, we seek to create an understanding, we desire connection, and we all need validation.

But it must start from within to be true to yourself. No one is creative at the wrong task. And creating or working toward something solely for the external validation is wrong. It will never lead to true fulfillment, and it will always leave you lacking. It’s like the desire for more money – at a certain point it is never enough, even when you have incomprehensible sums that could never be spent. At least that’s how it seems to go for the billionaires of the world.

A little while back, I bought a copy of Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act: A Way of Being.

I stopped on this page and pondered for some time:

No matter what tools you use to create,

the true instrument is you.

And through you,

the universe that surrounds us

all comes into focus.

I placed my bookmark in this page to come back to later.

My bookmark reads: We are stardust, meant to shine.

It’s true.

What Esports Organizations Can Learn From the NBA

All trends die.

Esports organizations today have it all wrong in chasing the quick dollars of limited-release apparel drops. They’ve often put the cart before the horse, in fact, trying to emulate the streetwear brand Supreme without understanding how long-lasting brands are built. They’re trying to become a trend, instead of something that seems baked into society itself; the way other sports have dug deep into the American way of life.

With no centralized league that dominates the scene, independent esports organizations like 100 Thieves, Cloud9, and Complexity Gaming will need to pick up the slack when it comes to spreading the message of these games and selling the merchandise that helps make the whole thing profitable.

Rather than emulate the likes of Supreme – choosing to sell hoodies to a select few who can afford to pay a premium for an average-quality cut of cloth – esports organizations should be following the lead set by NBA franchises, and the league itself to create an inclusive industry.

With COVID-19 shutting down major sports leagues, concussions still an ongoing concern in football and hockey, and representation in all forms of entertainment often lacking the diverse voices that companies so desire to reach, esports organizations and game developers need to take esports moment in the spotlight and make the most of it.

Esports are already huge, but they’re still growing compared to most traditional sports in terms of profits and longevity. The path to the kind of ubiquity enjoyed by football, baseball, and soccer involves treating current and potential fans as possible future players or at least ambassadors, rather than checking accounts that exist to be drained every few months. It’s about raising a whole new generation that sees esports as a part of life, not a novelty.

So why the focus on limited-edition gear from certain esports teams? Would the Bulls ever tell you that you can’t buy a jersey and become a walking billboard for your favorite team, player, and city? Of course not. So why would esports teams try building their own version of the Jordan brand without a Michael Jordan? You need to have the thriving league first, and then you can launch a premium brand that represents it.

The current attitude of exclusivity is at the root of the esports scenes fragmentation. The tribalism of past console wars has brought us to the Counter-Strike versus Valorant debate. Instead of growing a fanbase for a sport, the current approach creates a tribe member for Team Ninja or Team Shroud, and only goes after those who are already faithful. There are plenty of preachers, but the message tends to be aimed squarely at the choir.

And this approach is costing everyone money. While esports in general currently monetizes its fan base at less than $5 per viewer, compare to that to a baseline of $35 for traditional sports, and the fact that the NBA has been growing internationally for decades.

Talent development is the name of the game. The NBA develops players, referees, and broadcasters; this kind of attention to detail is important. More events and avenues to get involved means easier entry for more people, both as participants and viewers. If you just want to support your favorite team, there are ways to do so that fit every income level, whether that’s wearing a cap at home in front of the TV or screaming at the players from the arena while wearing nothing but branded clothes. If you want to start playing, there are onramps at just about every level of talent, for children and adults or just about every age.

The league also develops its fans, whether the fans realize it or not. Sports broadcasts are so sophisticated because they’re built around a combination of entertainment and education. Pre-game shows cover heartwarming stories and stats, but they also introduce fans to play styles, strategies, and Xs and Os. You can’t just show up and blow the whistle, you have to create an informed audience to consume the game and its products so they feel a part of the action.

Can esports do the same thing, but while focusing on what amounts to the logo, and not the players and fans? I don’t think it can, not for more than a few years anyway.

As Latoya Peterson questioned in an article for The Undefeated, “why are there so few other black players making it to the top of the various leagues?” While most professional sports – and even the fighting game community – manage to do better when it comes to diversity and representation, esports as a whole continues to struggle with making folks who aren’t straight white players feel welcome enough to give them a try, and it’s not news that the road to proficiency often filters players out due to the toxicity often found in online games.

But diversity on the court and in the stands is among the NBA’s biggest strengths. (In the boardroom is another matter, though.) For esports leagues to emulate this, they need to invest in training and development to ensure they reach players at a young age and teach them the skills to succeed, or at least make sure they have the tools needed to even try. Every local gym or community center has a basketball court, how many have the sorts of computers and accounts necessary to try Valorant?

The NBA hosts training camps and builds academies everywhere from the US to China, Africa, and India.

After cementing its place in China, the NBA has set its sights on India and Africa. The NBA views international expansion not only as a business opportunity, but as a “social responsibility.” How many organizations are even speaking in those terms? Meanwhile, they’ve set up a culture that deliberately focuses on broadening the tent, leading the initiative to launch the WNBA in an effort to give women more opportunities (though the league still has a long way to go for true equality to erase things like the pay gap), a development league, and the Jr. NBA focused on training young players the right way.

By only scouting talent from atop tournament leaderboards, rather than developing gamers from the ground up, esports organizations are missing a broad base of talent that could make their teams stronger and more diverse.

Investing in esports camps – much like the basketball academies being built around the world – could create a pipeline for talent who learn the fundamentals of gaming and how to carry themselves as professionals.

Where else can these younger esports find inspiration in the NBA? If esports organizations are ready to grow their teams on a global scale, toxicity must be eliminated.

After a swift investigation, the NBA issued two lifetime bans last year for fans using racist and derogatory language towards players. Toxicity in esports could be minimized by requiring players and fans to acknowledge a code of conduct before every event, and following up quickly when concerns are voiced. The gaming industry has shown positive signs as of late, with popular streamers being banned from Twitch for violating community standards, even when the actions don’t necessarily take place on stream.

With a few exceptions, instead of prioritizing the hard work of building trust and loyalty, many esports organizations have chosen to follow the most fleeting revenue stream and most fickle fans while ignoring the ways pro-sports leagues make money. NBA franchises make more than half of their revenue from arena and market income. That’s where they play and where they’re based, in other words. Why are there so few esports events that are accessible to the average fan? Why aren’t teams touring stadiums around the world so people can watch them play – and maybe even match up against them? After it’s safe to do so, of course.

The appetite is there. It’s been years since League of Legends sold out Madison Square Garden and the Overwatch League sold out Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York.

Why isn’t there an esports all-star game? Why aren’t they filling up arenas in Ohio, Illinois, and Texas, too? Why aren’t deals struck with ailing regional sports networks to air esports tournaments and other content?

The Cash App Compound, 100 Thieves crown-jewel of an office space in Los Angeles, could be host to clinics, events, and other development programs. Instead its stark industrial space is meant for retail, business operations, and content creation – often little more than advertisements for its brand sponsors. And sure, maybe they had grander visions for this space before we entered a world of physical distancing, but the fact of the matter is that most modern esports organizations thrive on this exact kind of exclusivity, not inclusivity.

It’s not enough to broadcast on Twitch and feed more money to the Amazon-owned service – game developers, teams, and even the gamers themselves need to support the launch of localized events focused on open access over hype – an organization like PlayVS has worked hard to make tournament organizing accessible.

With the right resources, the event framework could be replicated by schools and independent organizers in places beyond large markets. Make no mistake – this work has started, but it’s far from finished. And this is the kind of organizing it’ll take for the next generation to grow up with fond memories of esports leagues, like we do of youth basketball camps and soccer leagues.

But it can only happen with a commitment from more of the top teams to invest in this development. That’s what the NBA has that esports as a whole lacks: A single, dedicated force that profits from the entirety of the sport, while also making sure that sport maintains awareness and competitive players all over the world. There are many reasons why esports doesn’t have something similar, but those problems can, and must, be overcome.

Esports, and gaming in general, has always been a do-it-yourself world. Some games are intentionally cryptic, their difficulty a badge of honor when you’ve completed it.

But that doesn’t work if you want to grow a game on a global scale. Viewers and competitors need to be brought in and supported along the way – in other words, they need context – that’s one reason Rocket League is often cited as the biggest missed opportunity in esports. The conceit, soccer with cars, is as easy to explain as it is to watch.

Still, most esports are endlessly complex. Without context building being a top priority, even experienced viewers can find themselves behind the play. Commentators exist to break down plays and strategy, in esports it’s mostly talking about things that the experienced viewer already knows, and the uninformed viewer can’t follow.

“The NBA succeeded in monopolizing basketball globally in ways that the YMCA never could, thanks to its marketing of stars, the universality of its up-tempo, athletic game and its inclusion of a labor force that reflects its international fan base,” Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff wrote for The Washington Post.

It’s time for esports organizations to take advantage of this current opportunity, but they have to remember they are ambassadors for their sport, not companies trying to sell merch to survive.

The best Canon lenses you should buy

I've previously written about what lenses you should buy to build out your kit, and I only have one addition I'd make to that list today: the Canon 24-105mm f/4L. Although its low-light capabilities are lacking, it's super versatile, and with the built-in image stabilization, it can be more useful than the 24-70mm f/2.8 in some cases.

Recently browsing through The Wirecutter–a site I respect and trust for their in-depth reviews and emphasis on quality over junk–I was reminded of a comment I left years ago. It was on a review titled, "The First Canon Lenses You Should Buy." Since that list remains mostly unchanged years later, I thought it was a good idea to republish my comment here. Hopefully this finds people who aren't sure about what lenses to buy.

The following has been edited only slightly for context and clarity and refreshed for the best Canon lenses in 2019.

I was really surprised by the recommendations in this article. I'll preface my comment by saying I don't shoot photos, only video, but I shoot video exclusively on Canon DSLRs. I shoot with a 5D Mark III, 7D, 60D, and T2i. That said...

When people ask for lens recommendations, I always say: Don't throw away money on cheap or "passable" lenses. I would never tell someone to go buy a 5D Mark III and throw a 50mm f/1.8 on there.

Lenses can move from camera to camera. If you take care of a lens it can last a lifetime. A camera body will be replaced in what, 5 years? 3 years? For most purposes, you're better off starting with a cheaper body–a used T2i is (still!) a great buy (or similar but more modern entry-level model, depending on how much later you’re reading this, like the Canon 80D)–and then get the 50mm f/1.4. The 50mm f/1.4 will be a great lens even if you move up to a 5D Mark IV in a few years.

On a crop sensor body, you also may be better off (depending on your needs) getting a Canon 28mm f/1.8 or Sigma 30mm f/1.4 Art. These are also generally in the $300-500 range and will give you an image closer to a "true" 50mm on a crop body.

The 70-200 seems like overkill for this type of list. You should at least be comfortable with the camera before dropping $1000 on a lens. For that price range though, pick up an older model or used Canon 70-200 f/2.8L, a Tamron SP 70-200mm f/2.8, or the Canon 135 2.0L (a beauty of a lens that's often overlooked). The point being, put the money into a lens you're sure you'll use (and love) for years. Not something just so you can have a full kit.

The Canon 100mm macro is a very nice lens, but unless you specifically need the macro capabilities, an alternative there would be the Canon 85mm f/1.8. Another great lens that is sometimes under the radar, and perfect for portraits or staged interview setups.

Whatever lens you go with, the advice I try to ram into everyone's head is to look at your lenses as an investment. Camera bodies will be replaced. Spend the extra money (or save until you can afford it) for a lens that will last you a long time.

I will say I like the recommendation of using the 50mm f/1.8 as a relatively cheap way to find out what focal length you like. Good call.

How to Build a Creative Habit

A simple guide to help you better understand how creativity really works.

Creativity is not magic. It’s a habit you practice, built upon a mix of curiosity, passion, and determination. We all have at least a little bit of that inside us - remember that the next time you hear someone say, “I’m not creative.”

What the “I’m not creative” crowd might be doing is confusing creativity with skill. It’s OK if you don’t yet have the skills of your favorite authors, filmmakers, or musicians, but the process of learning and discovery is not out of reach to anyone with the will and ability to create.

There may even be benefits to creative pursuits beyond your own satisfaction. Dr. Cathy Malchiodi positions creativity as a wellness practice. She points to a number of studies showing how artistic practices contribute to wellbeing, especially later in life. “These findings underscore the idea that it is possible to build a ‘cognitive reserve’ through engaging in novel, creative experiences that have a protective effect on the brain,” notes Dr. Malchiodi. “Creativity is increasingly being validated as a potent mind-body approach as well as a cost-effective intervention to address a variety of challenges throughout the lifespan.”

If you feel like you don’t know where to begin, it helps to break the creative process down into smaller steps.

How to be creative (in five minutes a day)

In short, your goal is to start capturing life. You can write, take photos, knit, paint, carve wood, or do anything else that scratches your artistic itch. For simplicity, this will focus on writing, but you can apply the general principles here to just about any creative pursuit.

Dedicate five minutes a day to writing any thought that comes into your head. Write down a name, a stray phrase, or even what you ate for dinner last night. When you start looking at the same thing each day, whether it’s a blank page or your walk to work, you’ll begin to notice little differences. Repeating this practice each day creates a new muscle memory. As you repeat your process, you’ll become more comfortable and efficient. Dancer and author Twyla Tharp wrote about this in The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life, “It gives you a path toward genuine creation through simple re-creation.”

After you’ve been writing for ten or twenty days, start to think critically. There’s no right answer, but there is an answer. Which sentences do you like more? Why do you think that is? Every so often, spend your five minutes writing about which sentences are better and why.

At a certain point you’ll get bored. That’s good. Be comfortable with boredom. Dr. Sandi Mann found links between boredom and creative thought; by giving yourself time to drift mentally, you’ll come up with more unique solutions.

Once you’re in a routine, think about a new idea. This could be a poem, story, or blog post. Write it, but don’t be concerned about whether it’s good or bad. (Or if it even makes sense.) Put it in a drawer and forget about it. Write another one. Use your five minutes on this each day now.

Creative people have a lot of ideas. Most of them are bad. Most of them are put in drawers and never seen again. But only by going through all these bad ideas can they find the good ones.

Then apply your process to something else. Something bigger like a song, screenplay, or presentation at work. Because creativity works like a muscle, and you’ve spent a lot of time building it up, this will be easier now.

By stretching yourself toward something new, you can find new connections between old ideas. Tharp, in The Creative Habit, touched on the purpose of artistic endeavors: “Creativity is more about taking the facts, fictions, and feelings we store away and finding new ways to connect them.”

Remember: Being human means making mistakes. It's nothing to be ashamed of - making mistakes can be a great way to learn if you're receptive to feedback. This is where you’ll find gaps in your knowledge, or realize that your original vision was slightly off. If people criticize your work or you aren't happy with your progress, try to understand why. As Sarah Ruhl wrote in 100 Essays I Don't Have Time to Write: On Umbrellas and Sword Fights, Parades and Dogs, Fire Alarms, Children, and Theater, “Failure loosens the mind. Perfection stills the heart.”

Don’t set specific goals. Not yet, anyway. This might seem counterintuitive. Although you should be writing every day - which is kind of a goal in itself - don’t mark it on a calendar. You didn’t fail anything if you miss a day. You simply missed a day. On the other hand, once you've completed your goal, you might be inclined to stop practicing. That's not good, either. Being creative means figuring it out, not checking a box.

It will take time. That’s the point. As Mr. Rogers once said, “Discovering the truth about ourselves is a lifetime’s work, but it’s worth the effort.”

Every once in awhile, take a step back and look at how far you’ve progressed. This might mean looking through old work that makes you cringe, but it’s an important part of growth. By regularly assessing your own progress, you’ll be more comfortable constructively critiquing your future work as you create it. This helps you to avoid the same mistake twice, and will keep your eyes on where you have room to grow.

What comes next?

Creativity is about starting small, making mistakes, and constantly adjusting your work. In other words: Practice.

There’s a legendary story about director David Fincher’s 2010 film The Social Network. The opening scene between actors Jesse Eisenberg and Rooney Mara was filmed 99 times. As a viewer, you see a single version (or compilation from multiple takes) that makes Fincher, Eisenberg, Mara, and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin look creative, smart, and pitch perfect. You’re not seeing all 99 takes. You’re not seeing the dozens or hundreds of times Sorkin wrote and rewrote those lines. What you’re really seeing is the one time out of 99 they got each and every line just right. And that only comes after years, sometimes decades, of perfecting their craft.

What might you create if you tried the same thing 99 times?

How to Be An Artist

What is an artist, and how do you become one?

“I am interested in the artist who is awake, or who wants desperately to wake up,” Anna Deavere Smith writes in her book Letters to a Young Artist. To be an artist, in many ways, is to be a contrarian, and that can often feel like trying to wake up. From a young age we’re told no one can make it as a rockstar (despite all the rockstars we emulate with our air guitars), or that no one buys art anymore (despite all the paintings and photos hanging in our homes and offices), or that it’s impossible to make it in Hollywood (despite all the entertainment we watch every day). As we grow up, people constantly trash our liberal arts degrees, if we got one at all.

“An artist needs fight,” Smith says. That fight is why we show up every day despite the odds. And we’re in a fight, I’d argue, against complacency.

Whether you consider yourself an artist might depend on where you’re at in your career. Sometimes “artist” seems more like a lifestyle. Other times it feels like a label that can’t possibly apply when you’re working on passion projects in those spare minutes between jobs or diapers or whatever else fills your life.

But let me tell you this: You are an artist. Artists work with words, images, video, pixels, paint, metal, fabric, sound, code, and so much more.

Elizabeth Gilbert put it best in Big Magic: “You do not need anybody’s permission to live a creative life.” The doubters are just that: doubters. One day, they might come around and support you. But it doesn’t matter. Their permission isn’t needed.

Well done for making it here.

On paper, the job of an artist sounds easy: you find an idea and create it. This involves the discovery of exciting ideas and the process of refining and combining them into something new. But where do you manage to find ideas? What’s your method of creation?

The big secret is that you get to decide which tools to use. And the message is up to you, too. Find what speaks to you, whether that’s injustice in the world or the beauty in life’s small moments, and take those complicated ideas and communicate them in an interesting and succinct way.

“Art should take what is complex and render it simply,” Smith continues.

The goal of an artist is to find the essence of an idea and only include what’s necessary. An artist is an editor, a person who must have a sharp sense of focus on what matters, and the guts to ignore what doesn’t.

So, if you want to write a great essay, here’s how: Find a topic you’re passionate and knowledgeable about, then write 5,000 words on it. Reference films and books and music and whatever else inspires you. Then you just keep the great words.

Of course, it’s not that simple. But in some ways, it is. The work I do today is no different than the work I did ten years ago. What sharpens over time is the sense of what to keep and what to throw away.

Keeping only what’s great is a lesson the people who worked with Steve Jobs learned over and over again. Ken Segall, one of the creative directors behind Apple’s Think Different campaign and the “i” in iMac and iPhone, recalls some of those lessons in his book Insanely Simple. There’s one particular story that stood out to me - it was about a time when Apple was soon to release a new product. They needed a name.

The team had acquired the video editing software Color and they wanted to include it as an upgrade to Final Cut Studio. Jealous of Adobe’s naming style, they (seriously) considered names like Final Cut Studio 2 Extended Edition. Segall, fan of a simpler option, liked the name Final Cut Studio 2, With Color. There was a lot of back and forth with everyone fighting for their favorite version.

Until Steve Jobs walked in the room.

At the presentation, a full assortment of package designs, each with its own name, was neatly laid out on the table in front of Steve. The Platinum Edition had a nice shiny platinum stripe across the top. Each of the others had some feature that would help to differentiate it from the standard edition. Jan recapped the mission to set the context for Steve, telling him that this was being done to accommodate the addition of Color to the mix. Steve looked at the boxes, then looked up at the team.

“Put the software in the box,” he said.

The group was unsure what he meant. Explanation, please.

“Put Color in the Final Cut Studio box. We sell one product. Period.” There was a beat of silence as the group absorbed that. “What next?” he said.

Again and again, Segall comes back to this point: “Steve had rejected their work—not because it was bad but because in some way it failed to distill the idea to its essence. It took a turn when it should have traveled a straight line.”

He knew that fighting complexity is a key battle artists must win. It’s easy to keep an extra flourish because you like it; it’s hard to cut something you love because it's ultimately not needed. It's important to repeat, as Segall writes, “If you work harder and look more closely, there’s always something you can whittle away. It’s when you get to the essence of your idea that you’ll have something to be proud of.”

So, what’s the roadmap to being an artist? Today we know that “Work hard and everything will be fine” isn’t entirely true, so you can’t succeed just by working hard. There are a lot of hurdles that some people have to overcome that others don’t. And if you have a safety net, it’s easier to take risks. With that in mind, I’d like to suggest a different way to think about the overwhelming feeling of getting started: Big ideas are scary because we don’t know where to begin. It’s a lesson I took away from from James Altucher’s book Choose Yourself!

What that says to me is that you need to find the simplest place to start to make your art. Other steps will come later. For now start with a pen and paper, paint and canvas, computer and code - whatever is at your disposal. Once you’ve begun, steps two, three, and beyond won’t seem as daunting.

Think about it like this: If you say you could never write a book, you’ll never write a book. That one’s easy. On the other hand, if you set aside thirty minutes to write 500 words today, you can do it. That one’s possible.

To write a book 500 words at a time will take a long time - months, even years. But string together enough days of writing 500 words and suddenly you’ll have a novel’s length of passages and ideas. You can type one-handed into your phone while a baby sleeps in the other arm. You can write while you’re on the bus or airplane or sitting in the waiting room. You can write on your lunch break at your part-time retail job to prepare for your nighttime freelance gig. You can do this with a phone or a computer or a notepad and pen. I know because I’ve written in all those ways.

I graduated college during the great recession. In my hands was an expensive piece of paper and no job prospects to pay for it. So I worked in retail for years. Slowly, I found time to make my art on the side. I stayed up until 3 a.m. to work on freelance projects because those were the only free hours I had. I was exhausted, but I was making a go of it. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, or even where my skills were most needed. I was trying to figure that out.

Only half a decade later could I begin to find the themes I was exploring, to understand the skills I was building. The big, messy work was there to hold me over until I found the smaller great piece within, the story that needed the junk around it edited out. The next half a decade and beyond will be more editing, more learning, more exploring.

If you work that way - and you will have to work that way if you don’t get lucky or have a trust fund waiting for you - you can’t quit halfway through.

Artists keep going even when they’re told there’s no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. At the end of the rainbow is just a lot of dried paint to scrub off. To artists, making meaningful work is better than not making meaningful work, always. If you can afford to take that risk, you have to try.

And if you have to take a break for awhile, to take care of yourself, your work, or your family, know that your art will be waiting for you. It doesn’t judge. It’s alright to take a break for a few months, years, or decades. But do whatever you can to keep that spark alive until you are ready to return.

Before we get too warm and fuzzy, be warned that even if you make the brave decision to set out on your own, the forces of the world will tell you that you aren’t really an artist. You’re a businessperson, a schedule coordinator, a camera operator, they’ll say. Of course, those are reasonable skills to master, especially when you’re living paycheck to paycheck. But reducing your work to individual tasks moves you so far from your art that you can forget it’s art. Don’t let anyone make “artist” a dirty word, like it’s not real work, or the “art” is just the busy work in between other tasks.

You are an artist. Every stroke of a paintbrush or scratch of a pen is real work.

An artist questions everything, even the words you’re reading right now, because you recognize what works for me might not work for you. And that’s what sets an artist apart - that feeling in your gut that your mind won’t let you ignore. Even when you can’t articulate it, you know something’s there.

Understand that no amount of confidence or accomplishment will make the doubters go away. They’ll grow in volume and in numbers. Go look at the reviews for Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me or Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist. There’s never universal praise, no matter the connection a piece of art makes with its audience. Search long enough and you’ll find someone who hates your work or who wishes it had that one little extra piece (and then another, and another). It doesn’t matter. The only reason to seek out that unnecessary feedback is for your own ego. If you want to find the people calling you a genius, to read stories of how your work changed their life, to bask in the praise and demands for “more, more, more!” - go ahead. What you’ll find, even for great work, is negativity from someone, somewhere. And your brain will get stuck on that. Feeding your ego doesn’t matter because it always ends in frustration.

If you’re doing the right work, you already know it. The time you spend searching for criticism or praise is a waste. That’s time you could spend reading, or watching, or talking to people who matter.

This is why you always read advice that says to not take rejection personally. Rejected work often says more about the viewer than the maker. Don’t forget that. If you make art for the external validation, it will never be enough. In the words of designer Tyler Deeb, “Don’t chase the glory, work hard, and be satisfied.”

The work of an artist can be hard to quantify, which can be why so many don’t understand what we do.

Designer and writer Frank Chimero discusses knowledge work - or, work that relies heavily on thinking and processing information and ideas - in Other Halves, “Knowledge work has its name for a reason: the challenges naturally swing towards the cerebral, and doubly so if you work in design for digital products. You spend hours and hours considering ways to think about what is ultimately an immaterial thing. And who’s to know if it’s done or right?”

This is where every artist exists: “who’s to know if it’s done or right?” There’s never one right answer when it comes to art. Technique and skill are important - the settings on your camera, your use of light - but great pictures break fundamental photography rules all the time.

“Writing is a lot like that, too. So, on average, most of my waking hours are spent wrestling with ghosts,” Chimero concludes.

Artists consume the world around us, the garbage and the beautiful, and digest it into something meaningful. Song lyrics help lovers communicate their bond. A film helps a teenager escape from the confusing world around them. An essay helps its reader process tragedy and triumph. These are the ghosts we’re chasing. And they don’t exist unless we spend the time searching for them.

The process, when it feels right, is more about discovery than creation. These words are already there - the thoughts, the quotes, the arguments - the work I’m doing now is no harder or easier than the work I did yesterday. It’s just different. It’s connecting the pieces and comparing and contrasting them to what I’ve seen before.

I’ve made short films with friends since high school. From those days as a teenager all the way through my post-college freelance career, I worked with professional sports teams, championship-winning coaches, Olympians, national brands, and major universities to name a few. That’s not to brag or to polish up my résumé. That’s to confess this: I’ve never had a film accepted into a film festival. I’ve never even been to a film festival.

I’ve submitted to dozens - and probably spent too much money on admission fees - but I’ve been rejected every time. At first, it stung. The advice to not take it personally only goes so far after you’ve spent months, years of your life, and plenty of your money and energy making a piece of work that you want to share with people. And to be told you’re not accepted, in a way, feels like you’re told it’s not worth sharing.

But as I’ve said, an artist doesn’t quit. So what did I do when those first waves of rejections hit? Did I quit making films? Of course not. I put them online for free. Every one of them. Over half a million people have watched my films on the internet. I don’t need to get accepted into a film festival and show my film to a theater of a few dozen people to call myself a filmmaker. I’m a filmmaker.

A mystery panel of judges with their own biases and preferences says nothing about me and the quality of my work.

What skills do you need to be an artist? Well, first, here’s where you might struggle.

You might not be good with money, not because you don’t care, but because you’d rather spend what money you have on supplies for the next project. You might not be good talking to strangers, because you’re more comfortable spending that time with your thoughts and your work. You might not be the best salesperson, because it can feel a little bit slimy to sell part of your heart.

But you’ll be willing to listen and adapt. You’ll recognize that those skills are things you have to do to varying degrees to be successful. You’ll realize that art without commerce is a nice dream but impossible to attain. You’ll either need to sell your skills in another field to pay the bills, or you’ll need to sell your art. You’ll figure out how to make it work.

You don’t need any one particular skill over another to be an artist, except the desire to live a creative life and the ability to see it through. Beyond that, it’s up to you and what path you have the means to pursue.

To be an artist is simple: You show up, focus on what matters, and fight. Relentlessly.

Fiction's No Stranger: On Doree Shafrir's 'Startup'

Originally published by The Millions on April 26, 2017.

Art imitates life in tech, but novels give us one precious advantage over reality: the time to reflect on what we’re consuming.

Men in power have always tried to insulate themselves from criticism and punishment. Doree Shafrir’s Startup is a sharp-witted debut novel that peels back the layers of those structures, revealing those in power who grasp to maintain their privilege at all costs. The title signals an ordinariness that acts as a preview of what’s to come, a wink and a nod from a friend who asks if we see this, too. At its core, it’s a book about average men doing bad things and the women who take control of the narrative from them.